Decision Time

Some decisions don’t allow the luxury of contemplation. Every instrument pilot knows at least one of these decisions in the depths of his or her cloud-flying bones: the missed approach. Making a decision while still descending and a mere 200 feet above the ground (lower for Cat II+) only works because the decision is binary. You see the expected environment and continue—or you don’t and you climb away.

Pre-loaded decisions are a fantastic safety tool, but we so rarely need them that we end up unprepared to effectively use them. This applies to far more than a missed approach, but let’s start there.

Real-world instrument training under the hood leaves pilots woefully unprepared for a real approach with low visibility. This is possibly the best reason to get some real IMC time in training. One-half mile of visibility at 200 AGL on a typical three-degree glide path means you can see the approach lights peeking through the murk, the threshold, and some puddles on the pavement. Scratch the bit about the pavement if it’s night.

To immediately measure visibility the moment you break out, you must know what you expect to see. That’s your yardstick. Is this an ALSF-2 lighting system? Just a MALSR? Maybe this is a non-precision approach with an ODALS? (They’re out there. We have one just down the road from my home base here in Portland, Maine.)

Each of these systems are a different shape and different length from the threshold. You should have a minimum amount of lights on the far side you expect to see, which might include a certain number of runway lights when more visibility is required. You should know how far those lights extend from the threshold and how far you will be from the beginning of those lights. The point is you must know beforehand how much lighting you expect to see.

You should also know where to look. Crabbing down the localizer in crosswinds, pilots often forget that a ten-degree correction nose-right means those lights will be 10-degrees to the left. Anticipating that removes the moment of confusion when the lights pop-out off center. Or if the lights appear in a different place—or at a weird roll angle—you know something is wrong and a missed approach is the safest action.

The concept becomes more powerful if you expand its use. Take a non-precision approach with a published VDP. The VDP is the last point along the approach where you’ll likely be able to land straight-in without channeling your inner anvil. So know where that point is and watch it by distance on your GPS or by time. A breakout before that point is a pre-loaded straight-in. After that point, it’s a pre-loaded circle-to-land with a pre-chosen runway using a pre-planned path. Or, if you don’t dance circles, it’s a missed at the VDP. This is a decision gate: you have only two choices, and passing the gate only one remains.

This tool can be applied even more broadly. You’re on a base-leg vector to the localizer with a tailwind. At what point will you query ATC about a turn if one isn’t forthcoming? What would you do if the frequency was busy? Use the ident function on your transponder? If you were about to pass through, would you turn inbound or just keep going?

That last one is complicated and has been discussed in IFR Focus #1. But the point is that we can often predict moments where a decision must be made well before we get there. That means we can make an A-B plan, criteria for which option we’ll choose, and a point at which we’ll decide without hesitation.

There are so many places in regular flying where this happens: approaching weather and needing a deviation, requesting a new altitude before entering icy cloudtops, short final when struggling to stabilize the approach, floating on touchdown … it just goes on.

The takeaway on all of these is that a pre-loaded decision before you reach that moment of truth reveals actions that might make a snap decision unnecessary, as well as empowering you to make the right call without hesitation if you must.

Watch This Video:

“REACT: Five Takeoff Checks

That Could Save Your Life”

Thunderstorms and Mountain Passes

I learned to fly just south of Boulder, Colorado, and we routinely took 160-hp and 180-hp airplanes up into the mountains for destinations like Crested Butte, Telluride, and even Leadville. Nursing a flight-school Warrior over an 11,000-foot mountain pass is an exercise in patience that culminates with a decision gate.

You approach the pass riding the ridge for extra lift and at an angle to the pass. At the last moment, you decide if you have enough clearance to turn over the ridge, dive down for speed, and cross into the probably-descending air on the other side—or you peel away back around for another attempt.

Later in instrument flying, I found it useful to approach gaps in thunderstorms the same way, at least mentally. Space to turn around isn’t so critical, so approaching head-on is fine. But mentally there’s a distance to the towers on either side I want, and a certain visibility or clearance on the other side I require. That might be visible to the naked eye, or with the right on-board equipment. There’s a spring-loaded course reversal ready until I see what I need to commit on passing through the gap … or not seeing it and turning around to try another plan.

ForeFlight Question of the Month:

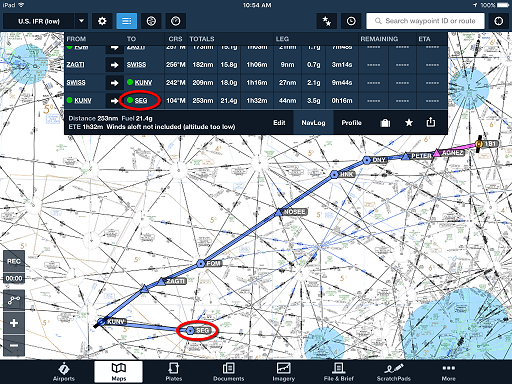

While editing your route you accidentally added a waypoint (SEG) that you didn’t want. What’s the quickest way to simply undo that last change?

A. Use the undo button. Duh.

B. Press-and-hold on SEG in the NavLog and choose “delete.”

C. Press-and-hold on SEG on the map and choose “delete.”

D. Switch to Edit mode, and then drag SEG out of the route.